Eye For Film >> Movies >> Who Will Write Our History? (2018) Film Review

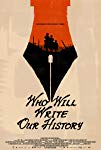

Who Will Write Our History?

Reviewed by: Jennie Kermode

Between 1940 and 1942, an estimated 92,000 Jews died in the 1.3 square miles of tenements that formed the Warsaw Ghetto. A further 307,000 died after being shipped directly from there to the concentration camps at Majdanek and Treblinka. Whole families were wiped out, leaving nobody to tell their stories. The Nazis intended to remove them not only from the face of the Earth but from history. In many cases they would have succeeded, were it not for the heroic efforts of a small group of people who ceaselessly collected and squirrelled away documents - personal histories, family photos, witness statements and more - to form the Oyneg Shabes Archive.

Telling the stories of the Ghetto and the archive side by side, Roberta Grossman's detailed documentary combines archive footage with dramatic reconstruction and retrospective narration. Nobody is likely to go and see this without expecting something grim, but parts of it are tough to watch nonetheless. Although the focus is on the Jews, we also get a picture of how their captor were changing psychologically, starting out simply as guards but gradually losing their grip as the situation drifted further and further from anything that could be perceived as normal. Their increasing cruelty, sometimes verging on the ritualistic, comes across like a deliberate attempt to go too far, to establish the boundaries of what had become an alien world.

Within that world, starvation was the biggest killer, and there photographs provide the most revealing testimony. Grossman compares the pictures and footage produced by the Nazis with that preserved in the archive, showing how a change in perspective alters the way the viewer understands the horrors depicted in both. In the Jewish material, those being victimised are always visibly human, as real and as complex as their tormentors. It's much easier for us to imagine ourselves in their position rather than as mere onlookers. The way that these images depict change is also valuable, letting us see how healthy, well dressed individuals became hollow-faced and ragged, how comfortable homes were reduced to bare boards as everything of value was traded for food.

The dramatic scenes are approached with a light tough, there for us to observe rather than directly engage with. Once again, they help to humanise those involved, to better understand the personal sacrifices made to protect the archive and the genius of its founder, Emanuel Ringelblum. Why focus on collecting stories when what people needed was food? Because by this point it was clear that vast numbers of people were going to die, but their stories could continue. Parts of the archive would go on to be used in evidence at the Nuremberg trials. They would find their way into a museum. They would speak for those who were lost.

These are portraits not just of death but of life, and Grossman's film strives to achieve something similar. A section on the difficulties of religious observance provides an insight into the cultural priorities of the Ghetto residents and their efforts to maintain their standards in the face of increasing pressure, and we also learn about Ringelblum's editorial approach and efforts to ensure that every piece of material for which he and his associates were risking their lives met a certain quality standard. The epilogue tells us what it all meant to those living in the aftermath.

Though it goes to very dark places, Grossman's film emerges as a story of triumph, a testament to the value and power of archive work, and a tale full of hope.

Reviewed on: 24 Nov 2019